I recently came across an interesting article in Volume 1, Issue 9 of Adventure Gaming Magazine from March, 1982 about implementing curses into fantasy RPGs. The article is titled “May Your Eyeballs Shrivel and Your Nose Fall Off: Effective Cursing in FRP” by Perry T. Cooper. I can’t find any information about the author other than another article in another issue of the same magazine. If you know anything about Perry, please let me know! I initially set out to rewrite the mechanics in this article as a PbtA move, but I actually think there’s something bigger to be discussed here re: curses as a narrative device in RPGs. So this is just a review of a 40-year-old magazine article, I guess.

The article opens with a short account of some gruff adventurers slaying their peasant guide to avoid splitting the gold found in the dungeon he led them to. The peasant curses them to never return from the cave with his dying breath, and the group of ruffians find their doom at the claws of a hungry dragon very shortly thereafter. It goes on to discuss the prominence of these kinds of curses in legend and folklore and their glaring absence in most fantasy roleplaying games. What follows is a valiant effort to systemize these kinds of curses in a way that “will add a new dimension to any FRP system (without intruding upon intricate rules systems or day-to-day-events).” Cooper divides curses into three categories of increasing severity. Type I curses are not fatal, and involve temporary inconveniences or humiliations. Type II curses can kill individuals, but no more. Type III curses can kill multiple people or curse entire bloodlines.

Each curse is presented as two percentile tables, one to determine the success of the curse placement and one to determine the penalties for placing it. Type I curses are the easiest, with a 60% chance of succeeding. Type II curses have a 45% chance of success, and Type III curses have just a 35% chance of succeeding. Even upon a successful curse, however, the curser has the chance to incur a penalty like disease, insanity, or even instant death. The steep penalties and risky probability serve to make cursing a last resort, but they also feel like they run contrary to the narrative purpose of curses identified in the article. After all, how many folktales involve a wronged person attempting to curse their oppressor and instead being cursed themselves, or who place a righteous curse only to be stricken blind. There is a stark conflict between what the mechanic attempts to do for the narrative and what the mechanic feels like it has to do in order to fit the system. The article ends with a phrase that further highlights this inconsistency.

“A curse is never intended to be an oft-used weapon; but for those who are ruthlessly oppressed, a curse can be the one means of striking back successfully at an oppressor.”

Perry T. Cooper, Adventure Gaming vol. 1 no. 9, pg. 35

This is such an incredible and evocative line, I love it. But contrast this with this passage from earlier in the article:

“Finally, curses are not all-powerful. They cannot be used to greatly alter the status quo; no person, great or small, can curse some great empire or religious group and then watch that nation or faith fall apart. Curses cannot be made retroactive; no curse will cause an adult to have died as a baby, or to never have been born at all. The past cannot be altered with a curse. And all curses can be broken or avoided if the cursed person is willing to perform the necessary labors (always difficult) and if the one placing the curse is still around to bargain with – if not, his/her spirit must be contacted for its terms, or a deity must be consulted. Curses have great power and can cause great trouble for any person, regardless of rank or power, but curses should never be permitted to grow so powerful as to take over any game system.”

Perry T. Cooper, Adventure Gaming vol. 1 no. 9, pg. 34

Curses are presented as a final resort for the oppressed, but explicitly cannot alter the status quo in a meaningful way. Why? Because doing so would mean messing with the structure necessitated by the dominant style in FRP games of the time. U2: Danger at Dunwater (side note, I’m going to review this module at some point. It’s so funky), published the same year as this article, would fall apart if the lizardfolk could put a meaningful curse on the sahuagin who drove them from their home. Or indeed, they could have cursed the human settlements that caused them to abandon their current stronghold generations ago. A misguided human who believed the lizardfolk to be the true threat, as players are meant to at the end of U1, could curse their society to ruin. But the existence of curses that could shift the balance of the status quo would disrupt the assumed gameplay of these games: that the characters are either defenders of the status quo or major agents of change.

This article makes an extremely astute assumption that curses are satisfying and cathartic narrative devices, but fails to imagine a world where a game could remain interesting and playable if these curses were allowed to function to their full potential. As the opening states, the curses in this book are designed to be powerful without “intruding on intricate rules systems or day-to-day events.” If a curse is to be a worthwhile strike against an oppressor, it by definition must intrude on systems and day-to-day events. Anything less is an impotent weapon in the face of oppression.

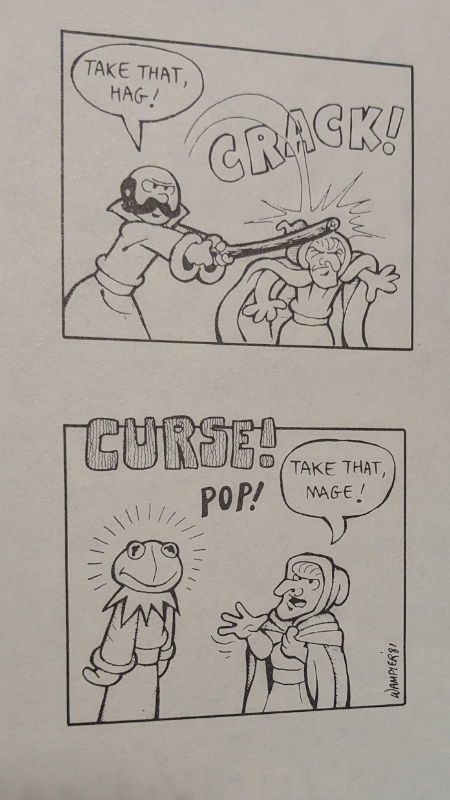

I hate to end this blog post on such a comical note, but the article does the same.