Whenever I am in a used bookstore, I am hunting for the RPGs. Usually there just aren’t any, but once in a while I’ll find a modest selection of 3.X D&D books, random other OGL-era d20 systems, or maybe some Deadlands or Cyberpunk Red. But what always catches my eye are the superhero RPGs. I can’t get enough of them. I think part of this is to do with the art; superhero RPGs often mirror the comic art style of the time, and comic artwork is extremely iconic and distinctive decade-to-decade in a way that isn’t always true for fantasy or sci-fi art. But I also am fascinated with these books on a mechanical level.

Superhero stories feel hard to model in a system where physical attributes have numbers attached to them. How can you possibly have enough numbers to give both Robin and The Flash a movement speed? How can the Captain America player feel equally matched in a combat encounter alongside the Hulk character? If my character sheet says I can, why wouldn’t I just take the fight straight to Lex Luthor? How a designer chooses to answer these questions says a lot about their priorities in telling a superhero story. In order to get a small cross section of superhero RPGs over the years, I’m going to flip through my collection of superhero RPGs in chronological order, starting with 1986’s Marvel Super Heroes and coming all the way back full circle to 2023’s Marvel Multiverse Roleplaying Game. These won’t be full, detailed read-throughs or reviews. I’m going to be focusing on the “What is an RPG?” sections and briefly looking at the power mechanics to get a sense of how the game is approaching the idea of superheroes. I might revisit some of these games later, but I want to get a bird/plane/Superman’s eye view of them all first.

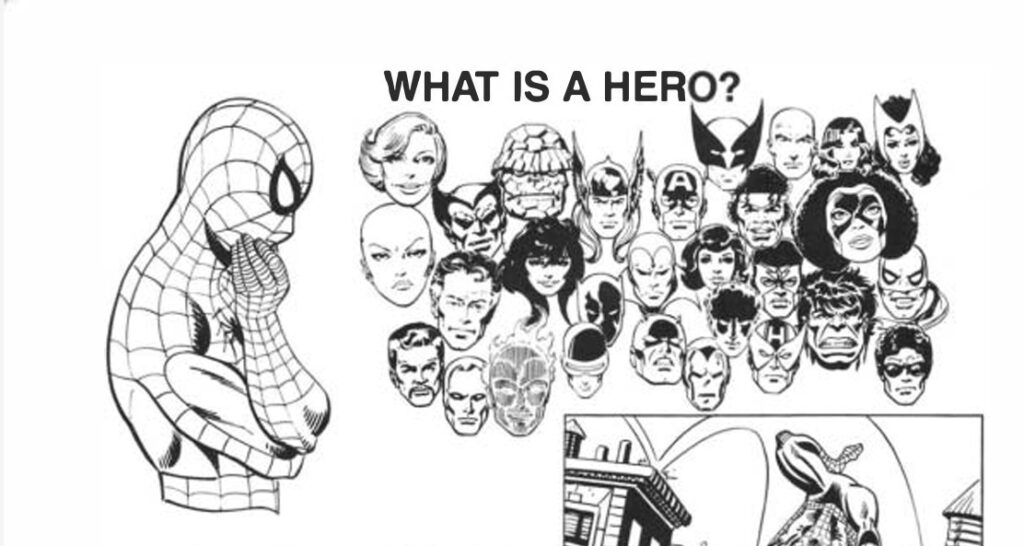

Marvel Super Heroes

The Marvel Superheroes RPG doesn’t have a “What is an RPG?” section, but it does have several “What is a Hero?” sections in its basic and advanced sets, as well as a “What is a Judge?” section. In the Battle Book, intended as the starting point for new players, Spider-Man himself tells the reader the following:

A lot of people think of heroes as odd, powerful weirdos who hang around in funny costumes and throw punches at villains. Actually, we’re just plain folks. Sure, our special powers make us a little tougher than your average Joe, but most of those powers are just normal abilities that have been tremendously improved.

(As an aside, that’s a wild definition of hero for someone who can shoot webs from his hands and climb walls. What “normal abilities” were improved there?)

Every hero, villain, and ordinary character in the Marvel Universe has seven abilities: Fihting Agility, Strength, Endurance, Reason, Intuition, and Psyche. Each ability describes how well that character can do something, like pick up heavy objects, dodge bullets and rocks, or beat up bad guys. These abilities are described below.

Marvel Super Heroes Battle Book pg. 2

The Player’s Book from the advanced set has a similarly mechanics-focused definition of heroes.

The Judge’s book goes on to define the role of the Judge, all of which is pretty standard RPG stuff. The Judge must:

Marvel Super Heroes Judge’s Book pg. 3

- Describe the situation to players, from the player-characters’ viewpoint.

- Answer the player’s questions and clarify statements.

- Role-play the various non-player characters (NPCs) the player-characters encounter.

- Handle game mechanics.

- Make rulings when called upon in game situations.

This section goes on to describe different scenarios the Judge will need to adjudicate, and therein we find a clue as to how this game views balance. In a section about using limitations to alter powers (like Nightcrawler’s Blending power only working in the dark), the books says: “Use the limitations to form the tenor of your own campaign, and to prevent Powers that are too strong from upsetting the balance.”

We find another clue as to the intended tone of Marvel Super Heroes’ in the section “Final Summary for Judges” on page 22.

Give the Players an Even Break: This has been said before, and it applies. The Judge has all the cards and most of the information. He knows where the hidden traps are and how badly wounded both heroes and villains are. Wiping out heroes wholesale is a problem, in particular with such world destroying guns as Galactus wandering around. Give the players a way out of that infallible Deathtrap (Marvel Super Villains are not infallible, though Judges usually are). Send in the Cavalry if the heroes are being too badly chewed up (but reduce their karma if they need Thor dropping by to handle a group of street toughs). Remember that the campaign is only as good as the Judge and players.

Marvel Super Heroes Judge’s Book pg. 22

So what’s the message here? Aim for balance in the mechanics, but don’t be afraid to put your finger on the scale narratively if needed. Don’t just wipe out all the heroes, even if the dice fall that way and the players’ plans don’t work out.

Marvel Super Heroes wants to define and clarify the heroes’ capabilities up front, and have the players and Judge use those defined stats to put themselves into the role of their favorite character. Captain America has Excellent Strength, which means he can lift a maximum of 2000 pounds with a successful roll. Cloak can teleport up to half a mile and Dagger can throw 4 daggers each combat round. Hawkeye’s quiver contains 36 arrow shafts; 12 standard shafts, 6 broad-blade heads, and the rest specialty heads. Presumably all these characters, in the fiction, do know how much they can lift, how fast they can run, and what their powers do. By defining all these so clearly, you are encouraged to play as the character, not just tell the character’s story. Add in the fact that all players are assumed to have an in-depth knowledge of the characters from the comics, and you have all you need to step right into their shoes. The game will play out like a Marvel comic because you’re playing Marvel characters. You know the role you’re meant to play.

I went into this expecting an old book like Marvel Super Heroes to be full of numbers, charts, parameters for simulating a world of superheroes. The design of the back covers certainly makes you think it’s going to be like that, they’re modeled to look like the Periodic Table for goodness sake. And while there is a decent amount of that here, it’s all in service of paving the ground for roleplaying. It doesn’t read like a descendant of a wargame in the way that D&D books of the time do. Instead, it feels like it’s trying to give you all the information you need to accurately roleplay as Spider-Man or Captain Marvel or Ultron.

Next time: 1989’s Champions: 4th Edition